2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine: how the immune system is kept in check

6 Outubro 2025

Escrito por Francisco H. C. Felix

Source: Nobel Prize Outreach 2025

Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell and Shimon Sakaguchi were awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for their discoveries concerning peripheral immune tolerance.” The laureates’ research clarified how the immune system avoids attacking the body’s own tissues — a mechanism essential to prevent autoimmune disease — through a specialized subset of T lymphocytes now known as regulatory T cells (Tregs Treg: short for regulatory T cells — a subset of T lymphocytes whose main function is to suppress excessive or autoreactive immune responses. Tregs maintain peripheral tolerance and prevent collateral tissue damage using multiple cellular and molecular mechanisms. ).

Summary of the findings

Mary E. Brunkow — Ph.D. from Princeton; key work identifying mutations that cause loss of immune tolerance in animal models; currently affiliated with the Institute for Systems Biology, Seattle, USA.

Fred Ramsdell — Ph.D. (UCLA); central contributions to identifying the FOXP3 gene and its relationship to autoimmune phenotypes; works as scientific/business consultant in biotechnology.

Shimon Sakaguchi — M.D./Ph.D. (Kyoto University); discovered the role of Tregs in peripheral tolerance and demonstrated how their absence or dysfunction leads to autoimmunity; professor at the Immunology Frontier Research Center, Osaka University, Japan.

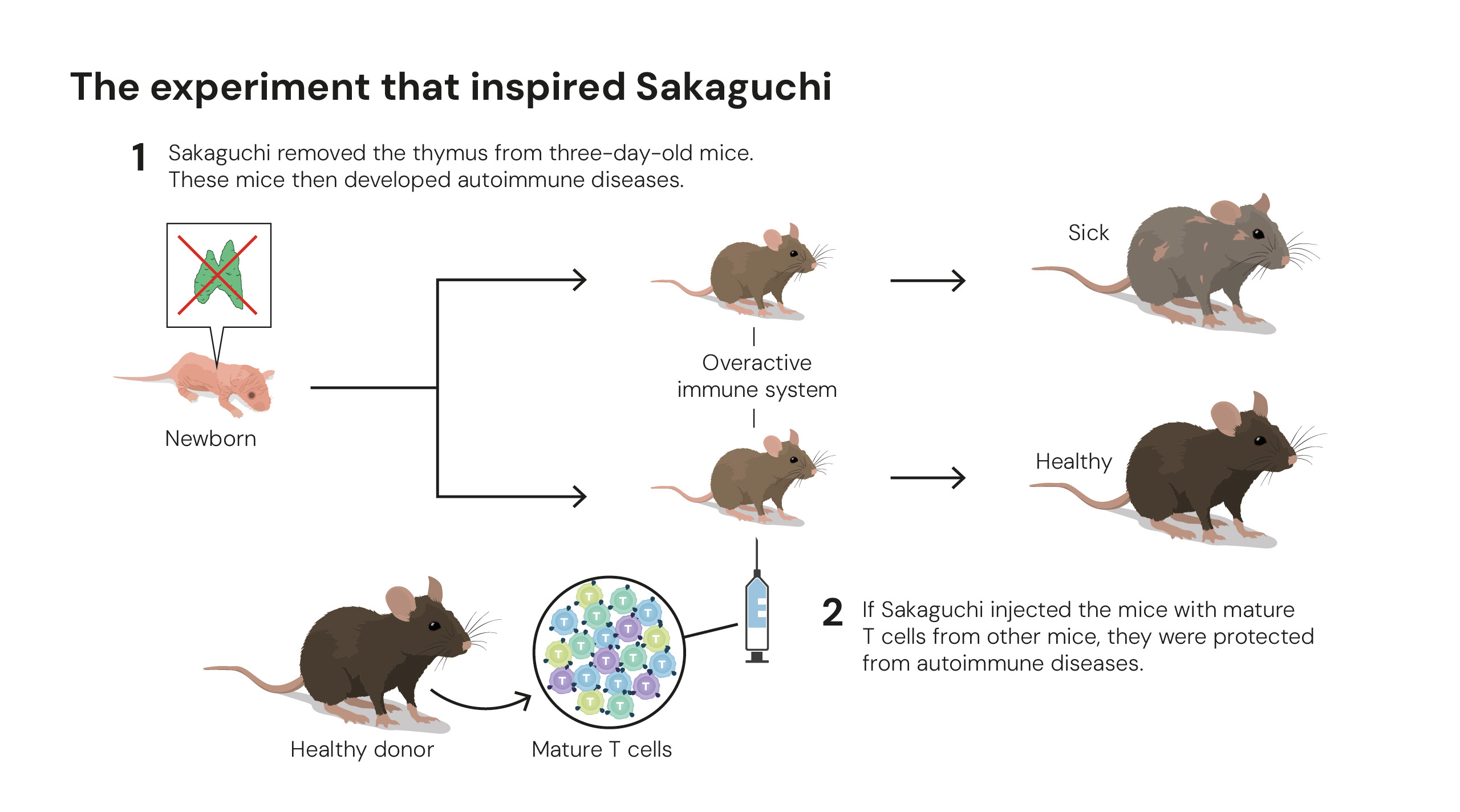

Shimon Sakaguchi made the first decisive discovery in 1995 by identifying a population of T cells with regulatory function — cells that limit potentially harmful immune responses. Later, Mary Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell identified the mutation responsible for an autoimmune phenotype in mice (the FOXP3 gene FOXP3: gene encoding a transcription factor essential for the development and function of regulatory T cells (Tregs). Loss-of-function mutations in FOXP3 lead to breakdown of immune tolerance, associated with severe autoimmune syndromes (e.g., IPEX in humans) and the “scurfy” phenotype in mice. FOXP3 controls gene expression programs that confer suppressive properties to Tregs. ) and showed that alterations in the homologous gene in humans cause severe autoimmune syndromes (e.g., IPEX IPEX (Immune dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked): a rare human syndrome caused by mutations in FOXP3. It is characterized by early-onset autoimmunity, severe enteropathy, endocrinopathies and other autoimmune manifestations; it often begins in infancy and follows a severe course without appropriate treatment. ). The link between FOXP3 and the development/function of Tregs established a new field of research: peripheral tolerance.

The laureates’ work changed our understanding of the mechanisms that prevent the immune system from attacking the organism itself. The implications are vast: manipulating Tregs is now a promising strategy both in autoimmune diseases (where the goal is to strengthen tolerance) and in oncology (where it may be necessary to dampen these cells’ action to improve antitumor responses). Moreover, advances in immune tolerance may make transplants safer and reduce the need for chronic immunosuppression.

Think of the immune system as an army whose job is to protect the body. To avoid collateral damage (for example, attacking the body’s own cells), besides training soldiers to recognize enemies, the body has oversight officers — the Tregs. They act as a brake: when the immune response is too strong or misdirected against self, Tregs intervene and tone down the reaction.

The awarded discoveries show:

1) that there is a specific type of cell whose main function is to suppress dangerous responses outside the primary formation site (so-called peripheral tolerance); 2) that a gene called FOXP3 is essential for these cells to exist and function correctly. Without FOXP3, the system loses its brake and attacks against self occur (autoimmune diseases).

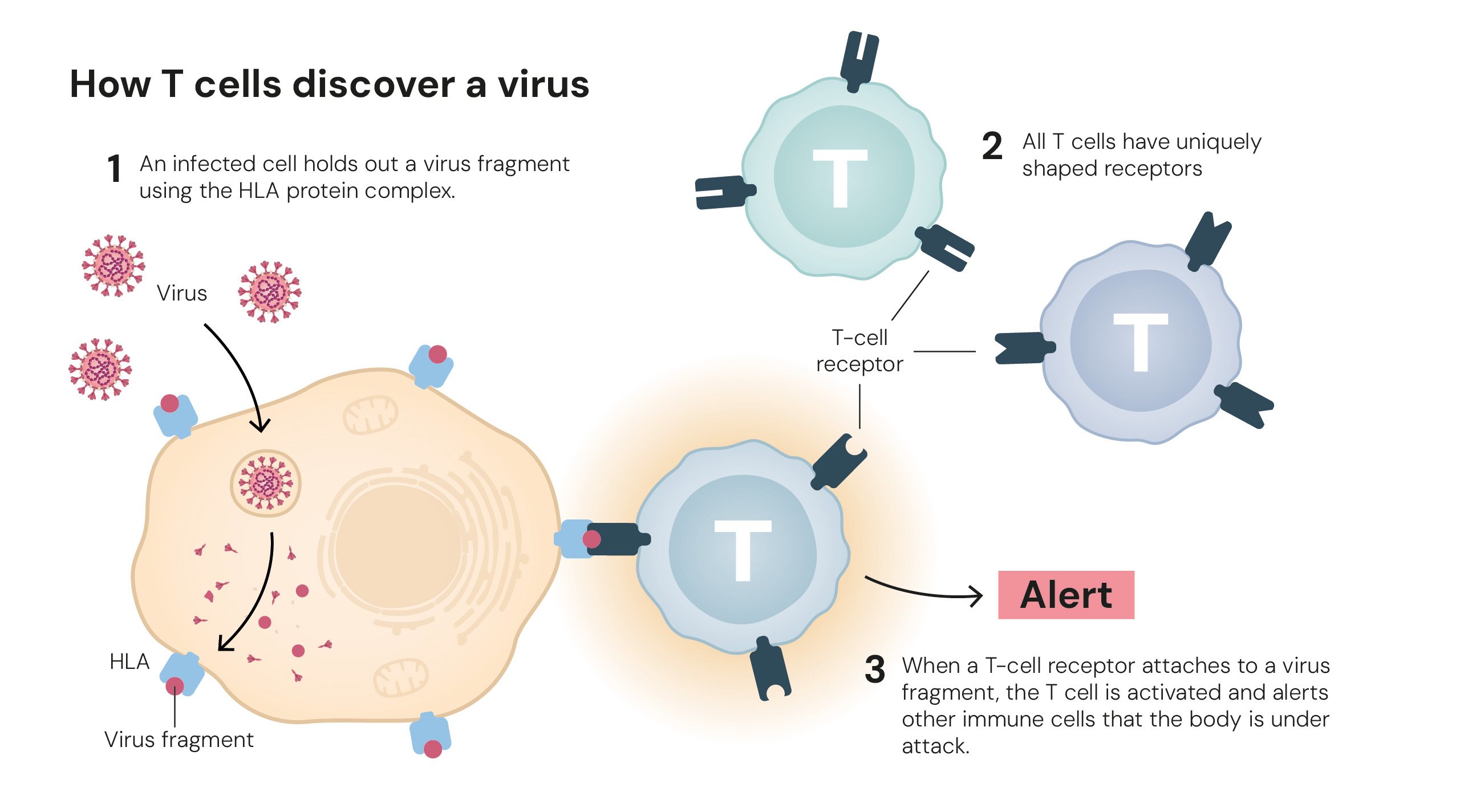

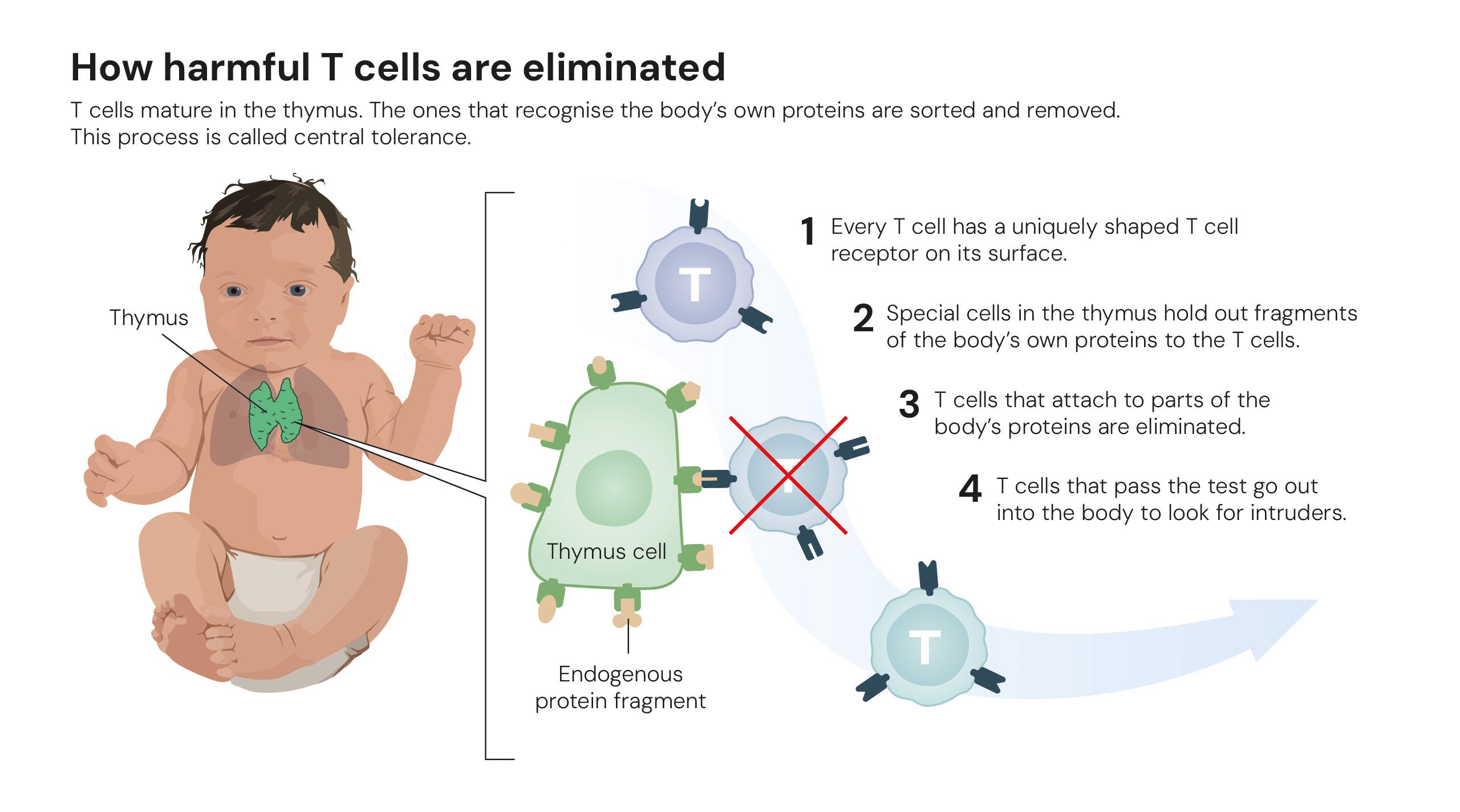

How T cells find a virus. Illustrations: © The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine. Ill. Mattias Karlén.

The most studied Tregs are CD4+CD25+FOXP3+. FOXP3 is the transcription factor that programs the fate and suppressive function of these cells. There are mechanisms of central tolerance (in the thymus) and peripheral tolerance (outside the thymus) Central vs peripheral tolerance: central tolerance occurs in the thymus during T cell maturation, where highly self-reactive clones are eliminated; peripheral tolerance refers to mechanisms outside the thymus that control remaining self-reactive lymphocytes, including regulatory T cells (Tregs). . Sakaguchi and others showed that part of the regulatory population is generated in the thymus, but that there are also peripherally induced Tregs derived from conventional T cells under certain signals (TGF-β, IL-2). Mechanisms of suppression: Tregs employ multiple mechanisms — production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β), expression of CTLA-4 that modulates antigen-presenting cells, local consumption of IL-2 (depriving other cells), and metabolic alteration of the microenvironment (e.g., adenosine production via CD39/CD73). Treg mechanisms: regulatory T cells suppress immune responses through several mechanisms — secretion of inhibitory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β), metabolic disruption of effector T cells, modulation of dendritic cell function, and direct cytolysis in some contexts. The relative importance depends on the tissue and the type of immune response.

Transfer experiments, mouse models with FOXP3 deletion (the “scurfy” phenotype in mice Scurfy mouse: an animal model with a loss-of-function mutation in Foxp3 that develops fatal lymphoproliferative autoimmunity early in life; this model was pivotal to demonstrate the essential role of FOXP3 and Tregs in maintaining immune tolerance. ) and clinical findings in IPEX (a human syndrome associated with FOXP3 mutations) were crucial to establish causality.

Experiment that inspired studies on peripheral tolerance. Illustrations: © The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine. Ill. Mattias Karlén.

Clinical implications and applications

Autoimmunity: understanding Tregs and FOXP3 allows identification of causes of syndromes such as IPEX, and points to strategies to restore tolerance in autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes).

Oncology: tumors often recruit or induce Tregs to suppress antitumor responses; modulating Tregs may improve the efficacy of immunotherapies (checkpoint inhibitors, vaccines).

Transplantation: Treg-based therapies (Treg infusion, protocols to expand them) are being tested to reduce rejection and decrease the use of broad-spectrum immunosuppressants.

Emerging therapeutics: approaches include ex vivo expansion of Tregs, engineering Tregs with specific receptors (CAR-Tregs CAR-Tregs: chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–engineered regulatory T cells are an experimental therapeutic strategy where Tregs are modified to express antigen-specific receptors, directing their suppressive activity to particular antigens or tissues (potential applications in autoimmunity and transplantation). ), and drugs that modulate key pathways (low-dose IL-2 to favor Tregs).

How harmful T cells are eliminated. Illustrations: © The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine. Ill. Mattias Karlén.

Read more

The main source for this post is the press release from the Nobel Foundation and the supporting materials published by Nobel Prize Outreach (official press release, scientific background and popular summary).

References

Popular summary, Nobel Assembly - in English (pdf)

Scientific background, Nobel Assembly - in English (pdf)