Early-onset cancer: the size of the problem and what we know so far

16 Junho 2025

Escrito por Francisco H. C. FelixIn recent years, the scientific community and the public have paid increasing attention to the global rise in early-onset cancer Cancer (from Latin cancer = crab): a large group of very different diseases, all characterized by incessant and disordered cell proliferation, the ability to locally invade healthy tissues, and the ability to spread to distant sites (metastasis). The various types of cancer theoretically originate from a single cell (clonal origin) that has undergone mutations in its genetic code. Learn more here. —defined as cancer diagnosed before the age of 50. The article by Ugai et al. (2022), published in Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology (DOI: 10.1038/s41571-022-00672-8), showed that although cancer was traditionally associated with people over 50, its incidence is becoming increasingly common in young adults.

What is early-onset cancer?

Early-onset cancer refers to tumors diagnosed in people under 50 years old. Within this group, there are important subcategories: adolescents (15-18/24 years), young adults (25-39 years), and early middle-aged adults (40-49 years). The internationally used term for adolescents and young adults is AYA (adolescents and young adults), generally covering ages 15 to 39. The impact of a cancer diagnosis at this stage of life is profound, affecting not only health but also social, emotional, and economic aspects.

The classification of early-onset cancer was introduced in recent decades after the observation that certain types of cancer, traditionally rare in young people, began to show increased incidence in adults under 50. This definition gained prominence from the 2000s onwards, especially in international epidemiological studies Epidemiology (from Greek epi = upon; demos = people; logos = study): the quantitative study of the distribution of health/disease phenomena and their conditioning and determining factors in human populations. It is a field of science that deals with various genetic, social, or environmental factors and conditions derived from microbiological, toxic, traumatic, etc. exposures that determine the occurrence and distribution of health, disease, disability, and death among groups of individuals. , to differentiate tumors that arise early from those that occur at older ages. The goal is to facilitate surveillance, research, and the development of prevention and early diagnosis strategies for this group, which has distinct clinical characteristics, risk factors, and needs.

A search for the term “early onset cancer” in Google Scholar (with quotation marks, to force the search for the complete term) shows the earliest mention in a 1974 article on breast cancer, which already compared the disease in women under or over 45 years old. The authors of this study were interested in the impact of known risk factors in patients with early-onset disease (supposedly more linked to genetic and hereditary factors Gene: a segment of DNA that encodes a molecule (usually a protein) with a specific function. Genes are the units of inheritance first hypothesized by Mendel and named by the Danish botanist Wilhelm Johannsen in 1909. Genes make up only a small fraction of a cell’s DNA; most DNA does not code for proteins and is not part of genes. The phrase “one gene, one protein” summarizes the central dogma of biology: genetic information is transferred from DNA to RNA and then to a protein. ) or later-onset (supposedly more related to habits and environmental exposure). They found that a family history of breast cancer seemed to be a risk factor for earlier cases, as well as age over 25 at first childbirth. Interestingly, later-onset breast cancer cases did not show a correlation with age at first childbirth. Thus, even in this 1970s publication, there was already a clue that non-hereditary factors were acting in the emergence of early-onset cancer cases. The corresponding term in Portuguese (câncer de início precoce) only appears in academic works (very few) after 2020.

The vast majority of scientific publications on this topic (“early onset cancer”), between the 1970s and 2000, focused only on hereditary cancer cases, related to known genetic alterations, and did not differentiate a specific age group, sometimes including children up to middle age. The greater emphasis on Ugai’s working definition (adults under 50) really came in the 21st century. But where does this definition come from? Why is 50 years the cutoff? There is no direct answer, but I found a very interesting 1983 study on hereditary cancer epidemiology and age at diagnosis, which tried, for the first time, to show that the occurrence of cancer in people younger than expected signaled some hereditary predisposition factor. The authors divided the group of patients they studied (with a family history of cancer) into groups according to the age of highest frequency of diagnosis for each cancer. The “young” group was bellow the 10th percentile of the age distribution and the “intermediate” group was between the 10th and 45th percentiles Percentile (statistics) in this context is a statistical measure that indicates the relative position of a value within an ordered data set. The percentile is the value below which a certain percentage of the data falls. For example, the 50th percentile (or median) is the value below which 50% of the data are located. If a student is in the 90th percentile on a test, it means they scored better than 90% of the other students who took the same test. The 10th percentile, on the other hand, indicates that 10% of the data are below that value. Percentiles are often used to understand the distribution of data and to identify outliers or extreme values. They are useful in various fields, such as education, health, and finance, to compare performance or characteristics between different groups or populations. . The median Median (statistics) is the value that separates the higher half and the lower half of a sample, a population, or a probability distribution. In simpler terms, the median can be the middle value of a data set. In the data set {1, 3, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9}, for example, the median is 6. age of the “intermediate” group was 53 years, and the mean was 49 years. Thus, it makes sense that the age of 50 has been used more frequently to differentiate early-onset cancer patients from the rest. Curiously, the 1983 study did not prove the correlation between family history (heredity) and early-onset cancer!

The importance of maintaining epidemiological surveillance in this age group is growing, as early diagnosis can significantly impact prognosis and quality of life. In addition, understanding the factors associated with the increase in these tumors can help guide public policies and preventive interventions.

How do we know incidence is rising?

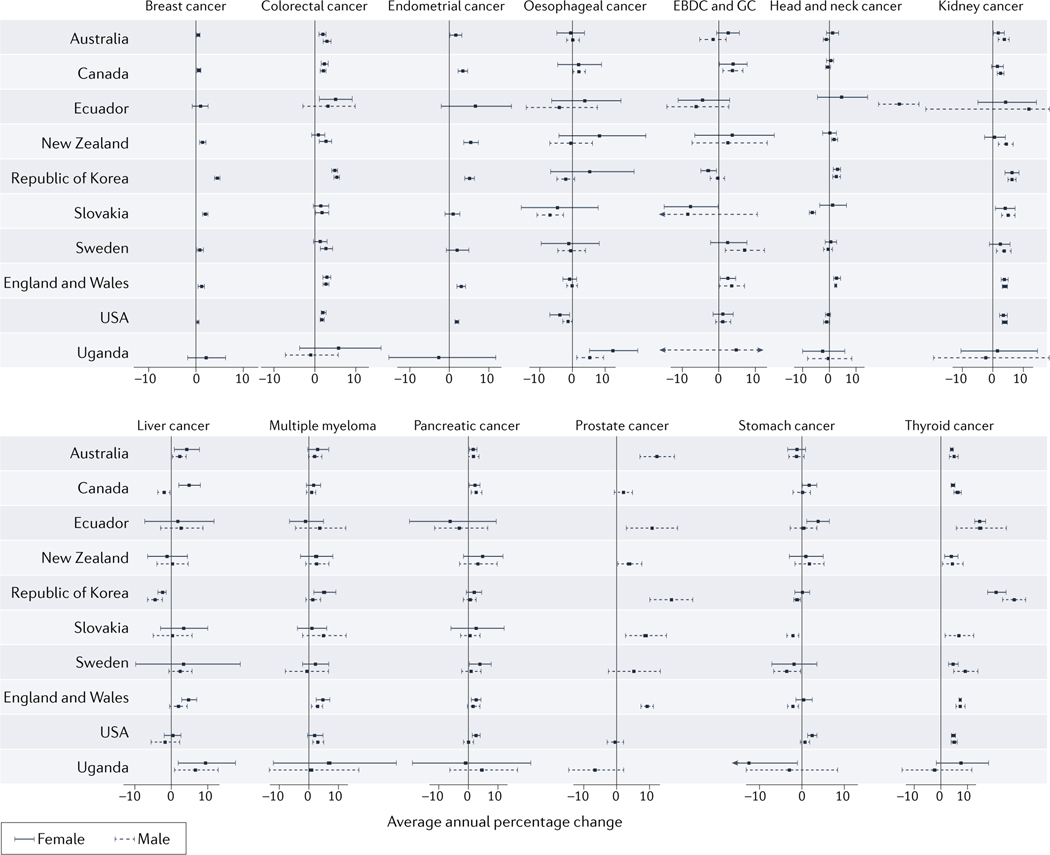

Multiple population-based cancer registries worldwide have shown a consistent increase in the incidence of several types of early-onset cancer since the 1990s. The Ugai article refers only to adults aged 20 to under 50, not children and adolescents. It analyzed data from the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) on 14 types of cancer in adults aged 20 to 49, in 44 countries, and found that between 2002 and 2012, there was a significant increase in tumors such as colorectal, breast, kidney, liver, pancreas, stomach, and others.

The authors calculated the average annual percentage increase in the incidence of each cancer during the study period. For example, the incidence of colorectal cancer in women under 50 increased, on average, by about 2% per year in Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Japan, the Netherlands, the UK, Turkey, and the USA. In Ecuador and South Korea, this increase was nearly 5% per year, indicating that this phenomenon was not restricted to developed Western countries.

Ugai et al. analyzed global trends and showed that the incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer increased consistently in several countries since the 1990s, both in developed and developing nations. The increase is observed even in countries without systematic screening programs for young adults, suggesting that it is not just a matter of greater detection, but a real phenomenon. This pattern is repeated for other tumors, such as breast, kidney, liver, pancreas, and stomach, as detailed in the review.

The review by di Martino et al. (2022) published in the British Journal of Cancer (DOI: 10.1038/s41416-022-01704-x) started from the observation of an increased incidence of colorectal cancer, especially in developed countries, and tried to confirm this for this and 11 other cancer types. They conducted a literature review published between 1995 and 2020, including 98 studies (68 from North America and 24 from Europe). Most studies reported only one type of cancer, 8 described several types. The meta-analysis showed that the incidence of colorectal cancer in adults under 50 increased by about 1-3% per year on average, in both sexes, in North America (in Canada, this increase reached 6-7% per year in those under 30). In Europe, the same trend was documented. This observation was more pronounced the younger the patient group (8% average annual increase in people aged 20-29 between 2004 and 2016). In Australia, the same pattern was repeated, but the data were less consistent in New Zealand. Another finding: cancer cases in people under 50 are more aggressive and diagnosed at a more advanced stage. This may be due to delayed diagnosis because of lower clinical suspicion in this age group.

Early-onset cancers of the breast, kidney, uterus, pancreas, bladder, and larynx are also increasing in several countries, as highlighted by both works. This growth is observed in both developed and developing countries, reflecting changes in risk factors and lifestyles, as well as possible environmental and behavioral influences. The di Martino review, however, showed a trend toward a reduction in the incidence of early-onset lung cancer.

The article by Sung et al. (2024) published in The Lancet Public Health (DOI: 10.1016/s2468-2667(24)00156-7) analyzed a population-based cancer registry in the USA. The authors used incidence data on 34 cancer types and mortality data on 25 types, in patients aged 24 to 85, diagnosed between 2000 and 2019. They compared the incidence adjusted by decade of birth, from 1920 to 1990. The study evaluated more than 23 million patients and more than 7 million cancer deaths in the period. They found that the incidence of 17 cancer types (small intestine, kidney and renal pelvis, pancreas, liver, intrahepatic bile ducts, breast, uterus, colon and rectum, stomach, gallbladder and other biliary tracts, ovary, testis, anus, Kaposi’s sarcoma) increased in people born more recently. As for mortality, it stabilized or decreased for most cancer types (except liver and intrahepatic bile ducts in women).

Additionally, the publication by Teng et al. (2024) in Science China Life Sciences (DOI: 10.1007/s11427-023-2445-1) evaluated the annual report of the China Cancer Registry, calculating incidence and mortality in patients with 25 cancer types between 20-49 years, from 2000 to 2017. The authors found an increase in the incidence of all combined cases of early-onset cancer, with an average annual increase of about 1.5%, especially in the youngest group. They also found a reduction in mortality in this group.

These data show that the phenomenon of increasing early-onset cancer incidence is global and not restricted to a few cancer types, affecting different regions and socioeconomic contexts, and not just the developed world.

Which cancer types are rising fastest?

Gastrointestinal tumors are the most notable for their increase, especially colorectal, pancreas, stomach, and, notably, biliary tract tumors (such as cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder cancer). The Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology article and Global Cancer Statistics 2024 data show that, in countries such as Canada, Sweden, the UK, and Bulgaria, the incidence of biliary tract cancer in adults under 50 increased on average between 3% and 5% per year, reaching 10% annual increase in Belarus (which, in a decade, amounts to a 100% increase in incidence!). Early-onset stomach cancer also grew significantly in the USA and Canada, reaching a 4-5% average annual increase in Northern Ireland, England, and Poland.

Early-onset pancreatic cancer, although still rare, increased its incidence by 1-3% per year in countries such as Australia, Canada, France, Sweden, the UK, and the USA. Liver cancer also increased, especially in Australia, Canada, Spain, the UK, Scotland, and Norway (in Ireland and Uganda, the increase was more than 9% per year!).

These regional differences seem to reflect both environmental and behavioral factors as well as screening patterns, diet, and infection prevalence.

Why is this happening? Main hypotheses

There is still no single explanation for the increase in early-onset cancer, but the various articles highlight several hypotheses. Below, we list the main ideas discussed in the recent literature, according to the sources we consulted. This is a quick overview; a more complete discussion of possible causes and associations with environmental exposures will be left for a second post.

Lifestyle changes: increased sedentary behavior, obesity, diets high in ultra-processed foods and low in fiber are pointed out as central factors in all articles analyzed.

Early exposure to environmental and behavioral risk factors: exposure to pollutants, passive smoking, alcohol, endocrine disruptors, and other environmental agents since childhood/adolescence.

Alterations in the gut microbiome: changes in the microbiome Gut microbiome: The gut microbiome is the set of trillions of microorganisms that inhabit the human gastrointestinal tract. The microbiome influences digestion, immunity, metabolism, and even the functioning of the nervous system. , possibly related to diet, antibiotic use, and cesarean sections, may influence cancer risk.

Use of antibiotics and other medications in childhood: suggested as a risk factor in several studies, but still with indirect evidence.

Genetic and epigenetic factors: although genetic syndromes explain few cases, epigenetic changes induced by environment and lifestyle are increasingly discussed.

Sleep, circadian rhythm, and exposure to artificial light: changes in sleep patterns and exposure to light at night may play a role in cancer risk, especially in urban populations.

Viral and bacterial infections: hepatitis, H. pylori, and other infectious agents are relevant for liver and gastric tumors in specific regions.

The article by di Martino et al. reinforces that most cases are not explained by known genetic syndromes, suggesting an important role for environmental and behavioral factors acquired in the first decades of life. The 2022 Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology article and the 2024 Science China Life Sciences article emphasize the role of the microbiome, diet, and early exposures as central factors.

Public health impacts

The rise in early-onset cancer represents a growing challenge for health systems worldwide. These patients have specific needs, may be underdiagnosed due to low clinical suspicion, and often face barriers to timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Strategies for prevention, early diagnosis, and research into causes are urgently needed. Prevention: set of actions and habits aimed at preventing the onset of diseases. For cancer, it includes not smoking, avoiding excessive alcohol, maintaining a healthy diet, exercising, and protecting yourself from the sun.

Perspectives: what to expect for the future?

There are still many uncertainties about the future incidence of early-onset cancer. Current data suggest that the upward trend may continue, especially if environmental and behavioral factors are not modified at the population level. However, understanding of the causes is still limited, and there is a need for longitudinal studies, investigations into early-life exposures, and research that integrates genetic, environmental, and microbiome data.

It is possible that, with greater awareness, public health policies, and advances in screening and prevention, it will be possible to reverse or at least slow this trend. On the other hand, without structural changes and more knowledge about the mechanisms involved, the increase may persist in the coming decades. Therefore, the scenario requires continuous epidemiological surveillance, international collaboration, and investment in multidisciplinary research.

Figure 1 from Ugai et al. (2022), Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology: Global incidence trends of early-onset cancers (diagnosed in adults <50 years) for 14 cancer types, 2002–2012, in 44 countries. Reproduced from the original article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). For full details, see: Ugai T, et al. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(10):656-673. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-022-00672-8

Figure 1 from Ugai et al. (2022), Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology: Global incidence trends of early-onset cancers (diagnosed in adults <50 years) for 14 cancer types, 2002–2012, in 44 countries. Reproduced from the original article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). For full details, see: Ugai T, et al. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(10):656-673. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-022-00672-8

References:

Ugai T, et al. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-022-00672-8

Sung H, et al. The Lancet Public Health, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(24)00156-7

di Martino E, et al. British Journal of Cancer, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01704-x

Teng Y, et al. Science China Life Sciences, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-023-2445-1