We Are the Memory We Have: Neuroscience of Memory

26 Junho 2025

Escrito por Francisco H. C. Felix“We are the memory we have and the responsibility we assume. Without memory we do not exist, without responsibility perhaps we do not deserve to exist.”

— José Saramago

Episode 60 of the TWiN (This Week in Neuroscience) podcast brought an in-depth analysis of the article published in Nature in 2025, presenting innovative discoveries about the cellular and molecular mechanisms of memory. The episode is also available on YouTube. The participants discussed not only the study’s results but also possible clinical and even philosophical implications of what I call “being the memory we have.” This theme was also discussed in Ted Chiang’s short story “The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling” (2013). In the story, he questions the accuracy of human memory.

Introduction: Why study memory?

Memory is one of the pillars of human identity, fundamental for learning, decision-making, and building our sense of self. Changes in memory are at the core of diseases such as Alzheimer’s, dementias, and psychiatric disorders. Understanding how memories are formed, stored, and retrieved is one of the greatest challenges in modern neuroscience. Neuroscience: The scientific field that studies the nervous system, including the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves. It investigates how these organs function, communicate, and influence behavior, emotions, and disease. As Oliver Sacks showed in his description of the musician Clive Wearing in “Musicophilia” (2007), “the memory we have” merges with our identity. Sacks described the case of a musician who, after a viral infection (herpes simplex encephalitis), lost the ability to retain new memories and almost all his past memories. The structures we know as the “hippocampus,” in the temporal lobes of the brain, were destroyed by Wearing’s infection. “He” survived, but his identity, who he was, was profoundly affected. Despite his severe deficits, he could still sing, play music, and recognize his wife. Something of himself remained, despite his injury and memory loss.

This real case, along with other real or fictional ones presented in literature (as in Chiang’s story), shows how memory is the basis of our identity, making Saramago’s phrase much more than rhetoric. It also shows how much we still have to learn about memory. Why do lesions in discrete structures like the hippocampus affect it so much even if the rest of the brain remains intact? Today, some answers are known, but much is still hypothesis and needs to be tested. The work presented by the TWiN team showcased one of these fascinating lines of research.

The study: New mechanisms of memory

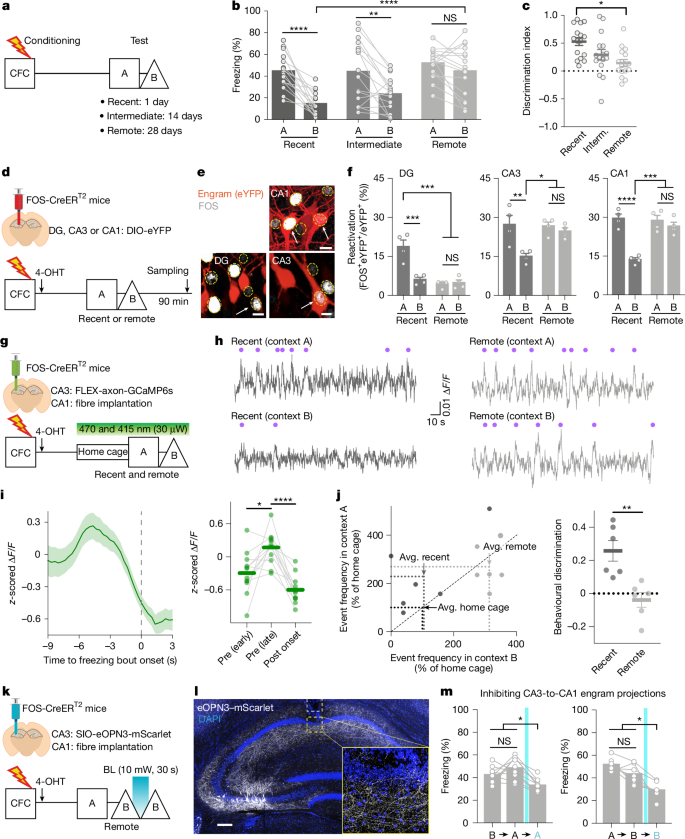

Figure 1 from the original article: Experimental scheme and main findings on the reorganization of engrams and memory generalization over time in mice. Source: Nature, 2025 (academic use, rights of the original author).

What is the hippocampus?

Hippocampus: Brain structure located in the temporal lobes, essential for the formation and consolidation of memories, especially contextual and spatial ones.

The hippocampus is a brain structure essential for the formation, consolidation, and recall of memories, especially contextual and spatial ones. Located in the temporal lobes, it is part of the so-called limbic system and is highly conserved among mammals.

Its basic structure consists of three main regions: dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1. The information flow follows a well-defined path: the dentate gyrus receives the initial stimuli and transmits them to the CA3 region, which in turn projects to the CA1 region. This “trisynaptic” organization is classic in memory studies.

In the experiment discussed in the podcast, hippocampal activation was assessed both by animal behavior (freezing response) and by techniques of neuronal activity recording and optogenetic manipulation. The researchers focused especially on the connections between CA3 and CA1, showing that the reorganization of these connections is related to memory generalization over time. In addition, techniques such as GRASP allowed visualization of specific synapses between engram neurons in these regions, revealing structural changes associated with consolidation and loss of memory specificity.

What are engrams?

Engram: A set of neurons that store a specific memory, being activated during learning and recall of that memory.

The concept of engram was proposed in the early 20th century by German biologist Richard Semon, who suggested that memories would be stored as “physical traces” or lasting changes in the brain. For decades, the term remained more theoretical than experimental. From the 2000s onwards, with advances in genetic and optical techniques, it became possible to identify, label, and manipulate specific populations of neurons activated during memory formation — the so-called engrams.

Currently, engrams are defined as sets of neurons that are activated during an experience and that, when reactivated, can evoke the memory of that experience. Experimentally, researchers use gene activity markers (such as the Fos gene) and tools like optogenetics to identify and manipulate these neurons in animal models. This allows testing whether artificial activation of these neurons is sufficient to retrieve a memory, or whether their inhibition prevents recall.

In this work, the use of engrams was fundamental to investigate how memories become less specific over time. By labeling neurons active during learning and tracking their reactivation in different contexts and times, the authors demonstrated that memory generalization is associated with the reorganization of engram circuits in the hippocampus.

The experimental model and the experiments performed

The study analyzed in the episode used contextual fear conditioning Contextual fear conditioning: Experimental model in which an animal associates an environment with an aversive stimulus, used to study associative memory. in mice as its basis, one of the most classic and robust paradigms in behavioral neuroscience to investigate associative memory. In this model, the animal is placed in a new environment (context A) and receives an aversive stimulus (usually a mild foot shock). After this pairing, the animal learns to associate the context with the unpleasant event. In later tests, when placed back in the same environment, the mouse exhibits a freezing response, interpreted as an indication of memory of the aversive event. To assess the specificity and generalization of memory, animals are also tested in a different context (context B), which was not associated with the shock. The difference in freezing behavior between contexts allows inference of the degree of memory precision or generalization (Garelick & Storm, 2005).

In the discussed work, this paradigm was used to investigate how memory becomes less specific over time and how hippocampal circuits participate in this process. The main experiments involved:

Temporal assessment of memory: Mice were tested at different intervals after training (one day, two weeks, and 28 days) to investigate how memory specificity changes over time. Initially, animals freeze only in context A, but after 28 days they also freeze in context B, indicating memory generalization.

Engram mapping: The authors genetically labeled neurons active during fear conditioning (engrams) and analyzed their reactivation during memory recall in different contexts and times. Initially, there was greater overlap between neurons activated during training and recall in the original context (A), indicating high memory specificity. Over time (28 days), this overlap equalizes between contexts A and B: the same engrams are reactivated in both, reflecting memory generalization. The study also showed that generalization is associated with a reorganization of the engram circuit, making it more “promiscuous” (less specific).

These results reinforce that engrams are not static, but change over time, accompanying the transformation of memory from specific to generalized, and that processes such as neurogenesis Neurogenesis: The process of generating new neurons in the adult brain, especially in the hippocampus, important for memory plasticity and flexibility. and synaptic plasticity Synaptic plasticity: The ability of connections between neurons (synapses) to strengthen or weaken in response to activity, enabling learning and brain adaptation. play an active role in this dynamic.

Circuit recording and manipulation: Calcium indicators and optogenetics were used to record and manipulate the activity of CA3-CA1 hippocampal circuits, showing that generalization depends on these circuits. Inhibition of these pathways reduces freezing in both context A and B.

Synaptic analysis with GRASP: An innovative technique allowed visualization of synapses formed between engram neurons. Surprisingly, after 28 days, there are more synapses between CA3 and CA1 associated with the engram, and these synapses become more clustered, suggesting structural reorganization of the memory circuit over time.

In addition to results on circuits and synapses, the study investigated the role of adult neurogenesis (formation of new neurons in the hippocampus) in memory generalization and specificity. The authors showed that when neurogenesis is blocked (by radiation), memory remains specific even after 28 days: animals freeze only in the original context (A), not generalizing to context B. On the other hand, when neurogenesis is stimulated (by exercise), generalization occurs earlier: animals freeze in both A and B at the intermediate time, as if memory had become less specific more quickly. That is, neurogenesis accelerates engram restructuring and loss of memory specificity, while its absence keeps memory more precise.

The authors interpret that memory generalization mediated by neurogenesis may be an active and adaptive process of the brain, not a failure. This suggests that adult neurogenesis helps make memories more flexible and generalizable over time.

Results and comments from the hosts

The results show that, over time, memory becomes less specific and more “promiscuous,” that is, the animal begins to generalize the fear context. The hosts highlight that this may be an adaptive feature of memory, allowing past experiences to be used to predict similar future situations, even if not identical.

Jason Shepherd comments that generalization is not simply forgetting, but an active reorganization of memory circuits, possibly advantageous for survival. Timothy Cheung points out that forgetting can be an active and necessary process, and that the observed synaptic plasticity may explain why old memories become less precise.

In this sense, the concept of “memory extinction” Memory extinction: Process by which a learned response (such as fear) decreases when the aversive stimulus is no longer presented, involving the formation of a new safety memory. may relate to the general findings of this new experiment. Memory extinction, according to Garelick & Storm (2005), is a process by which a conditioned response (such as fear learned in a context) gradually decreases when the aversive stimulus is no longer presented repeatedly in that context. That is, the animal learns that the previously dangerous environment is now safe, and the freezing response disappears. This process is not simply the forgetting of the original memory, but the formation of a new safety memory that competes with the fear memory. Changes or failures in this extinction mechanism are associated with disorders such as anxiety and PTSD, in which aversive memories persist pathologically.

In Chiang’s story, for example, he recalls the story of Solomon Shereshevsky, a Russian journalist active in the 1920s. The writer uses his case as an example of the problems that an “excessively” precise memory can bring to people. In fact, Shereshevsky had a unique ability to memorize based on a very pronounced synesthesia and its use to create cues and mnemonic formulas. He truly had a prodigious memory, but it was not true that he could not, or did not, forget. However, it is a fact that the frequent use of his abilities brought him mental health problems, such as anxiety and confusion.

The hosts also discuss the controversy over the stability of engrams and the transfer of memory from the hippocampus to the cortex over time. Questions remain to be explored about the dynamics of engrams over time and how the activity of these circuits correlates with the activity of other brain areas. A point raised by Vivianne Morrison and commented on by Jason Shepherd was that engrams can change over time in different experimental models, and this “drift” is not well explained. Shepherd discussed that, although observed in other experimental models, engram drift is controversial and it is believed that, in the contextual fear conditioning model, engrams seem to be stable. He also commented that, in this model, it was possible to detect the activation of 10-20% of hippocampal neurons after conditioning, but the final engram must be much smaller than that, as shown by the 10-15% overlap of cells activated during memory retrieval. The mechanisms responsible for long-term memory storage in the cortex still need to be clarified.

Questions and reflections raised in the episode

In addition to the experimental results, the episode brought important reflections:

Memory and identity: To what extent are we defined by the memories we keep? What happens to the “self” when memories are lost or altered?

Chiang discusses in his story how it is possible that the memories we keep are summarized and idealized versions of the facts we actually lived. Literature is full of examples of the “Mandela Effect,” or the supposed generation and persistence of false memories collectively. I will not discuss this subject here, as it is not necessarily related to the research theme. However, the effect of memory reorganization observed over time is complex and well known in psychology, and the discoveries described in this work may add another element to the neural mechanisms behind this, in addition to already known phenomena such as the consolidation and reconsolidation of long-term memories, as well as memory extinction.

Plasticity and forgetting: Is forgetting an active and necessary process? How does the brain decide what to keep and what to discard?

A possible implication that did not arise in the discussion of this work and that I did not find in the literature concerns human creativity. The process of creation is complex and multifaceted, but it is possible to see a possible participation of a neural mechanism that turns a specific memory into a generalized memory. The ability to generalize from observations is crucial for generating new scientific knowledge, being a pillar of the inductive method and its derivatives. A mechanism like the one described in this work, in which a memory recorded for a certain context can be generalized to others, could itself (or some related or similar mechanism) be related to the ability to learn and generalize learning and form new knowledge in humans.

Significance for science and society

The study represents an important advance in understanding the biological mechanisms of memory, showing that the consolidation and reorganization of neural circuits are dynamic and adaptive processes. This highlights the importance of dialogue between science, philosophy, and ethics in the face of rapid advances in neuroscience.

What is TWiN?

TWiN (This Week in Neuroscience) is a podcast dedicated to discussing the latest advances in neuroscience, with participation from renowned experts. The program is part of the MicrobeTV network and is available at microbe.tv/twin.

TWiN Team

- Vincent Racaniello (Columbia University, USA)

- Jason Shepherd (University of Utah, USA)

- Timothy Cheung (New York University, USA)

- Vivianne Morrison (Tulane University, USA)

All participants and collaborators contribute to the qualified debate on neuroscience in the podcast.

References

- Original article in Nature

- TWiN 60: We Are the Memory We Have

- Episode on YouTube

- Garelick & Storm. PNAS, 2005

About the initial quote: The phrase that inspires the title of this post is by José Saramago, Portuguese writer and Nobel Prize for Literature. Saramago wrote these words in his book “Cadernos de Lanzarote I”, reflecting on the importance of memory and responsibility in building individual and collective identity.