What is cancer

1 Março 2017

Escrito por Francisco H. C. FelixSiddhartha Mukherjee, physician and writer, called cancer Cancer (from Latin cancer = crab): a large group of very different diseases, all characterized by incessant and disordered cell proliferation, the ability to locally invade healthy tissues, and the ability to spread to distant sites (metastasis). The various types of cancer theoretically originate from a single cell (clonal origin) that has undergone mutations in its genetic code. Learn more here. the “emperor of all maladies” in his best-selling book. If diseases were measured by deaths, however, tuberculosis would undoubtedly be the emperor, having caused over a billion deaths throughout human history. Nowadays, with increasing control of infectious and cardiovascular diseases, cancer stands out as the leading cause of human deaths. In 2012, more than 8 million people died of cancer worldwide.

But what is cancer? It was named by ancient anatomists because the lesions burrowed into the flesh, forming “fingers” or “legs” that deeply invaded surrounding tissues, resembling a crab. To begin with, cancer is not a single disease.

There are hundreds of different types and subtypes of cancer. Until the 1990s, differentiation between them was mainly based on the site of origin and the type of cell they arose from, or, in technical terms, their anatomopathological appearance. Since the end of the Human Genome Project Human Genome Project (HGP): an international consortium that involved more than 5,000 researchers from 50 countries, aiming to sequence the entire human genome (the set of all genes). Planned since the 1980s, it began in 1990 under the direction of James D. Watson (one of the discoverers of the DNA structure) as a program of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and National Institutes of Health (NIH). The project was expected to take 15 years and cost $3 billion to sequence about 100,000 genes. In 2003, a joint press release announced the official completion of the project, which sequenced 99% of the human genome with 99.99% accuracy, finding about 22,300 genes, much fewer than initially expected. in 2003, the genetic alterations behind the various types of cancer have been mapped in increasing detail. The Cancer Genome Project has already mapped the main genetic abnormalities of the most frequent types of cancer. This opened the possibility for molecular classification.

When I was a student, I learned that cancer is a cellular disease, but this definition has been modified by new knowledge. As someone recently said, in the last 10 years, we have learned more about cancer than in the previous 1,000 years. So, we can update the definition to cancer is a molecular disease.

We are all made up of cells Cell (from Latin cellula = small room): the structural and functional unit of living organisms. The English scientist Robert Hooke described what he called “cells” in his 1665 treatise Micrographia, observing plant tissues under a microscope. He thought the structures resembled honeycomb, hence the name. Today, we know that all living beings are made up of one (unicellular) or many (multicellular) cellular units (cell theory, first stated in 1839 by Schleiden and Schwann). The cell consists of a membrane surrounding a gel called cytoplasm and a structure called the nucleus where the genes are located. , an astonishing 37 trillion of them, more or less. How do they manage to stay cohesive in an organism that remains unitary and perceives itself as an individual for decades? This is one of nature’s real miracles, which we hardly notice. One of the most surprising things about living organisms is that this enormous number of cells does not remain static. They have much shorter lives than the organism they inhabit, so they need to multiply throughout our lives.

Our blood cells are renewed every 120 days, on average. Our skin is renewed every 30-40 days in adults (ranging from 2 weeks in babies to two months in the elderly). The intestinal epithelium is even faster, renewing every 4-5 days on average! Even bones go through this process: in the first year of life, we “replace” our entire skeleton, and in adults, bone renewal is about 10% per year. Neurons are one of the very few cell types that do not renew in mammals. In fact, during growth, we lose a certain number of neurons in some brain areas (there are still doubts whether some are renewed or not).

This means that, although we maintain our physical and psychological individuality, in practice, every ten years or so, we “change bodies” (except for neurons). This renewal rate is higher in childhood and decreases in the elderly. Our cells, then, are in a constant state of division and multiplication, even in adults. It is estimated that, in a human lifetime, about 10 quadrillion cell divisions occur—more than 40 times the number of stars in the Milky Way! This is impressive and explains the main source of genetic mutations in our cells: the cell division mechanism itself.

When a cell divides, it must copy all its genetic material Genetic material is what exists inside a cell and carries the information about the characteristics of a living being. The inheritance of traits from parents to offspring has been known since ancient times, but only in the 1850s-60s did the Czech scientist Gregor Mendel study inheritance patterns in detail and suggest that hypothetical elements (later called “genes” by Johannsen in 1905) were responsible for heredity. The nature of these genes remained unclear until it was demonstrated in the 1940s-50s that deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is the molecule responsible for genetic inheritance. . That’s no small feat. The human genome Genome: the complete genetic material of an organism. It includes all genes, non-coding DNA sequences (which are not genes), and also the genetic material in organelles such as mitochondria. For example, the 22,000 human genes make up less than 2% of the human genome. consists of 22,000 genes Gene: a segment of DNA that encodes a molecule (usually a protein) with a specific function. Genes are the units of inheritance first hypothesized by Mendel and named by the Danish botanist Wilhelm Johannsen in 1909. Genes make up only a small fraction of a cell’s DNA; most DNA does not code for proteins and is not part of genes. The phrase “one gene, one protein” summarizes the central dogma of biology: genetic information is transferred from DNA to RNA and then to a protein. spread across 3.3 billion base pairs of DNA DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid): a complex organic molecule, DNA is a polymer—a chain made up of simpler molecules. It is composed of four types of molecules: adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine, which are nucleotides, the monomers (individual parts) that make up the DNA polymer. Each DNA molecule consists of two long strands of nucleotides that coil into a double helix. The order of nucleotides along the DNA strand is not random; it forms a code, called the genetic code, which stores the information needed to produce all the proteins in a cell. In fact, the DNA in each cell contains the information necessary to reproduce the entire organism. (the DNA molecule is divided into basic “bricks” called bases, which are copied one by one during cell division). The process of copying the cell’s genetic material is one of the most tightly controlled biological phenomena. After all, ensuring as few mutations as possible is critical for our survival. Even so, with all the protective mechanisms in cells, it is estimated that 0.1 to 1 mutation Mutation (from Latin mutatio = change): in biology, alterations of the cell’s genetic material. Mutations can be classified in several ways. For example, silent mutations do not change the expression of the genetic code and therefore have no effect on cell structure or metabolism. Point mutations involve the change of a single nucleotide in the chain, while deletions remove a part of the chain and insertions add a segment of nucleotides. occurs in each genome replication. This amounts to at least 1 quadrillion genetic mutations in a human organism over a lifetime! The vast majority of these mutations, however, will not cause cancer.

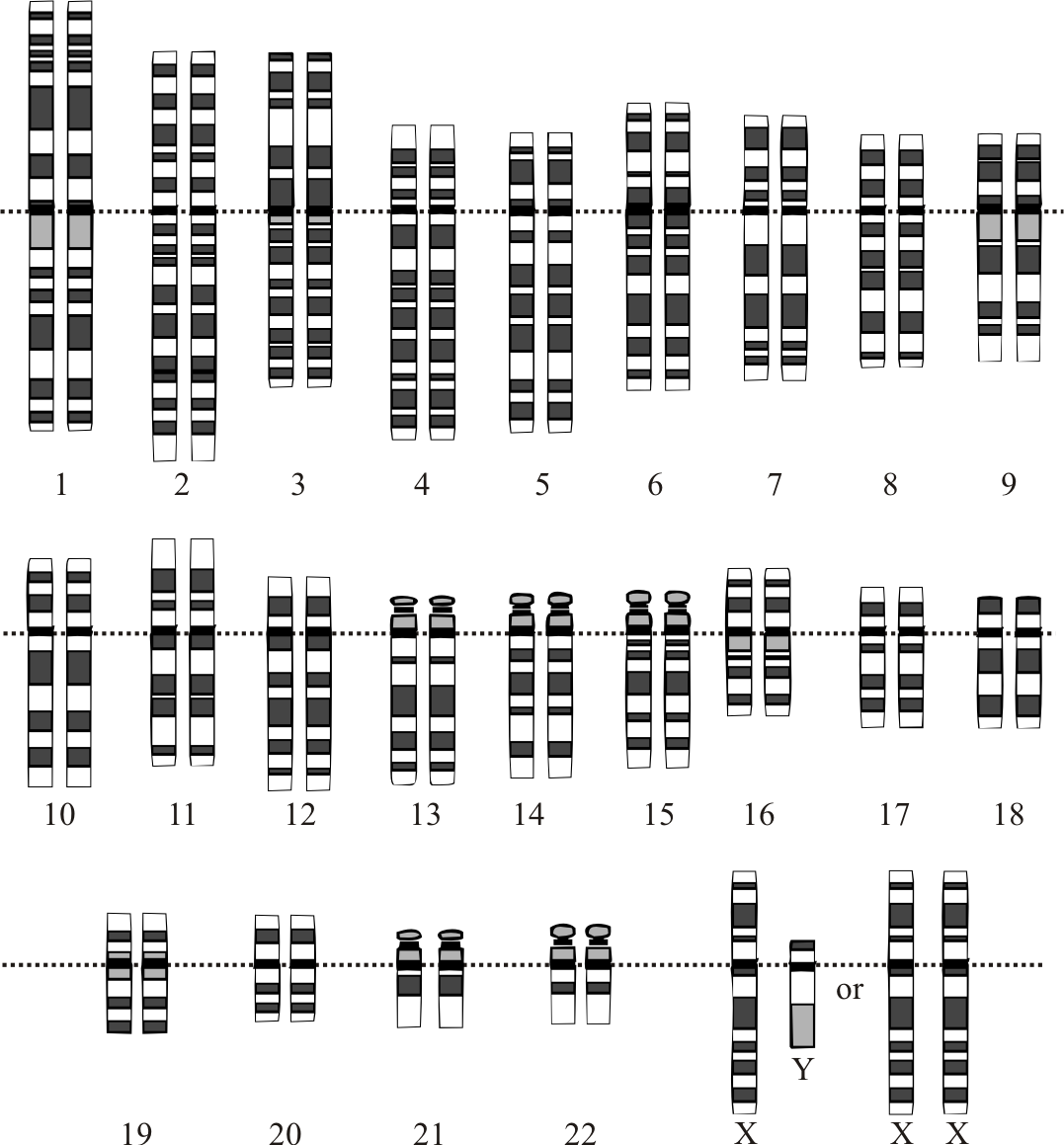

Figure: the human karyotype (set of chromosomes). Credits: National Human Genome Research Institute (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons.

Most mutations will have absolutely no effect, as the genetic code is highly redundant. Moreover, most of the base pairs in human DNA do not code for any gene. So, only a small fraction of mutations will impact cell physiology. Even then, not all of these impacts will alter cell growth. Only mutations that change how cells control cell growth (the cell cycle) can cause cancer. It is estimated that about 1,000 genes control the cell cycle, so only a small fraction of genetic mutations that actually affect cells will have the potential to alter the cell cycle and cause cancer.

Figure: DNA base sequence damage by UV radiation from sunlight. Unprotected exposure to UV rays is one of the most important causes of skin cancer. Credits: Mouagip (derivation) DNA_UV_mutation.gif: NASA/David Herring. This image was created with Adobe Illustrator. (DNA_UV_mutation.gif). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It is very difficult to estimate the number of genetic mutations with the potential to cause cancer that occur during a human lifetime, but that number is certainly large by any perspective, probably in the order of many millions. This leads us to the current scientific theory about the origin of cancer: it is a byproduct of normal cell division in living organisms. This means there is no real cause of cancer; it occurs randomly, by chance. It’s like playing the lottery all your life—the chances of winning are small, but eventually, some “win” the cancer lottery. This also makes us wonder why cancer is not much more common! Today, the main hypothesis is that the immune system spends its life “hunting” and destroying cells with the potential to cause cancer (transformed cells) in our bodies. This explains why, recently, modern treatments that use the body’s own immune system (immunotherapy) have been so successful.

So, to summarize, cancer is not a single disease; it is a large group of very different diseases, caused by genetic mutations that occur naturally throughout everyone’s life. Some questions arise. Why does exposure to environmental factors increase the chance of getting cancer? The answer relates to the theory of cancer. UV radiation from the sun, chemicals, X-rays, and other forms of radiation increase the chance of cells having genetic mutations by damaging DNA. A diet rich in carbohydrates makes the body produce a lot of insulin, and insulin stimulates cancer cells and increases their survival against the immune system.

This leads to a final conclusion: it is possible to greatly reduce the incidence of cancer by reducing exposure to environmental factors such as sun, smoking, alcohol, and carbohydrates, but it is impossible to reduce the incidence of cancer to zero. So, will cancer always exist? “Always” is a strong word, but it is reasonable to think that, in any foreseeable future, cancer will continue to exist. However, it is indeed possible to greatly reduce its incidence with simple and inexpensive measures, but that is a subject for another post.